06 Sep Abel escapes ritual murder in Tinnaka, flees

Abel spent the next day preparing for his assignment. By nightfall, he had memorized the profiles of his subjects, including top government officials, leaders of the majority party, their families and their key aides.

The most important player was Gorem Huud, the executive governor of Tinnaka State. Huud had a master’s in engineering and had been general manager of the National Airports Authority. Leaders of the ruling Peoples Party in Nigeria had lured him into politics. He was not one of the popular governors in the country, and he knew it. Consequently, Huud had a reputation for being quick to accuse those around him of disloyalty. Abel wondered if this made him more prone to corruption. If Huud doubted the long-term possibilities of his office, he might well be tempted to grab all the graft he could while he had the opportunity.

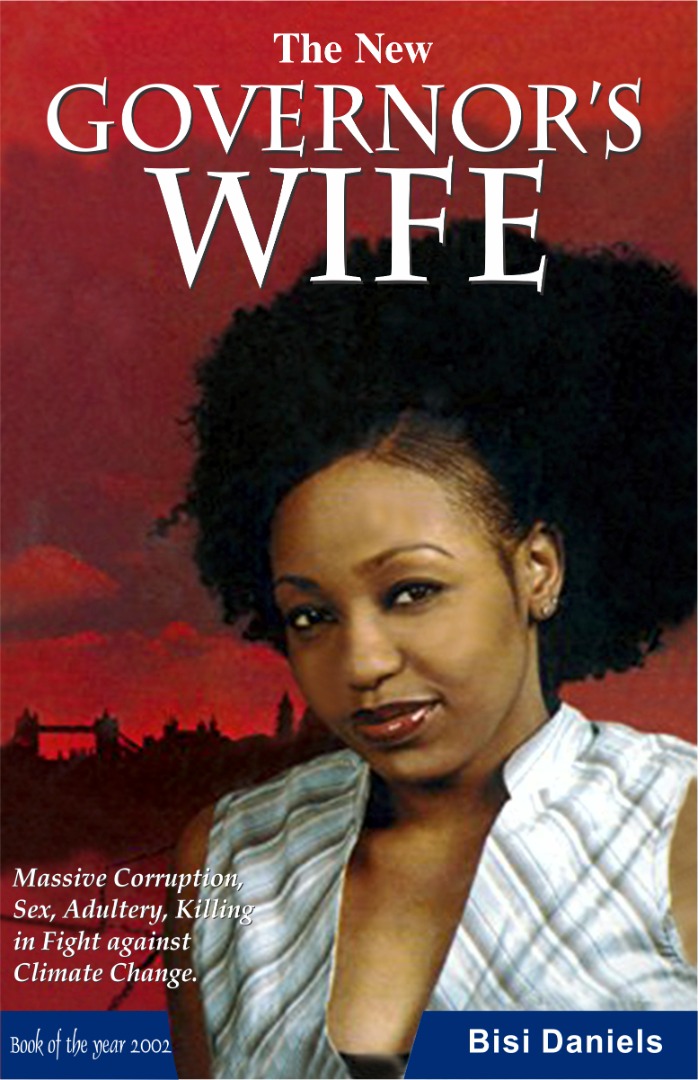

Abel was almost as fascinated by Huud’s notorious wife, Rika. Her statuesque beauty made her a natural source of interest to the press, especially because she was also known to be a shrewd businesswoman. She owned a number of supermarkets in Bammak City. But it was the darker side of Rika that drew Abel’s attention. His sources, speaking only on assurance of complete anonymity, told Abel that Rika was a jealous and greedy woman, and that she had a voracious sexual appetite that Gorem Huud could not begin to satisfy. One source, a cocktail waitress, said she had been part of an orgy organized by the governor’s wife. The waitress said one never crossed Rika. She was ruthless, capable of anything. She warned Abel to be careful when dealing with her. There were rumours she had ordered the murder of a man who had planned on running against her husband. Abel nodded at the advice. A predator! Still, she might be useful. Predators are aggressive by nature and that means they can make mistake, expose themselves. Abel filed this information away.

If governor Huud was indeed corrupt, stealing money from the government – especially if the money was from the Federation government or donor countries – Abel knew the man’s inexperience in government dictated he must have partners, or even handlers who guided the process. But who were these puppeteers who made the governor dance? The cover of Mario Puzo’s classic novel, The Godfather, flashed through Abel’s mind. When Abel remembered the scene where Sonny Corleone was slaughtered at a tollbooth, his body riddled with bullets, he shuddered. Not because the book made him queasy, but because he was stepping into the Nigerian version of this world. And death here was the real thing, not the work of make-up artists.

Abel pondered the situation on a Saturday morning as he chain-smoked in his study. Sprawled on a rug, smoking his eighth Marlboro Light, he wondered what he would find in Limi. He had little information, and it made him feel naked and exposed. Worried, his head aching mildly, he made a blind attempt to crush the remaining third of the cigarette in the ashtray above him.

If only Camp could have told him more. Why did he have to be so damned crafty? But Abel answered his own questions. If he made too direct a beeline for the culprits, if he wrote stories without making noises and investigating, the guilty parties would know he had been fed the information by an insider, one very high up at that. And Camp’s reputation for integrity and outsider status within the inner circle would make him a likely suspect. It was a crazy game that had to be played.

It was almost funny. Abel had to draw fire to protect his most valuable inside source. But that made him highly vulnerable.

He was exhausted already, and he’d only been gathering background and tapping sources for 24 hours. “I need a long session at the gym,” he muttered and broke into a coughing fit. It was only at such moments of self-inflicted pain that he remembered the ministry of health’s advice about cigarettes. The warnings had little effect on smokers in Nigeria. It was a cultural reality that people smoked. Those who had money found it chic. Those in the middle class used cigarettes as a cheap source of relaxation. A low-cost narcotic. Among the poor, who were dying of so many other diseases, telling them to stop smoking was like telling a drowning man to stop swallowing water.

Abel finished another cigarette, inhaling deeply just to demonstrate he wasn’t afraid of dying. He needed courage; because in the back of Abel’s mind, doubt crept in. He looked at the cast of characters, the corrupt governor, his nympho wife and a dying people living on a dying part of the planet, and he knew this would be no ordinary story. This would be the story of his life. If he lived to write it.

á á á á á

The taxi ride to the airport and the flight to Tinnaka State were uneventful. Behind his dark Armani glasses, Abel confirmed that nobody on the plane or at the Maxi Hotel in Bammak City had a special interest in him. Sooner or later, his interest in the story would be noticed by Huud’s and Tiko’s aides who knew him from the election campaign and his special series, “The Forces behind the Candidates,” in The Zodiac. But he wanted to work undercover as long as possible.

The next morning, Abel hired a Suzuki 345 motorcycle and headed out on the hot and dusty road to Limi. It was the only hint Dr. Camp had given him, and he hoped it would lead to something besides a sore rump from the bumpy ride. The road was full of potholes and the landscape arid and barren. Thirsty emaciated cows stood by the side of the road, searching in vain for blades of grass or puddles of water. Stick figure villagers squatted beside them, having no better luck sustaining themselves then the hapless animals.

Life in Limi would not be any different. Once prosperous, it was now a poor village in this semi-arid part of the drought-stricken state. It was Camp’s hometown and a symbol of the state’s failing agriculture. The dust-laden air and the cracked soil devoid of vegetation were clear signs of the people’s pain. Wherever Abel looked, even as far as the beckoning horizon, he saw the same heat, drought, thirst and poverty. His skin burned in the scorching sun and the hot, dusty wind.

Abel rode past a couple and their two daughters, who all turned for a quick look at him. The man, wearing a brownish white gown and carrying a black staff as tall as he was, strode ahead. His wife and teenaged daughters wore faded ankle-length gowns and carried sundry provisions in large bundles. Petty itinerant traders, Abel told himself, and felt his stomach churn as the mother who walked behind ordered the children to hurry after their father. Child labour was an African problem fuelled by poverty.

Now abreast of them, Abel greeted the man and asked if he could help, although he knew such an offer from a stranger would be refused.

“No,” he said and gave a hostile wave of his hand. The man’s bent back belied his height. Not wanting to attract unnecessary attention, Abel waved good-bye and sped off. Shortly after, he heard the traders shout for joy. Surprised, he slowed down and noticed the sudden atmospheric change.

He heard thunder, and then he felt a cool, soothing wind. He removed the dark glasses and found the sky turning grey. The darkening cloud cover might herald the long awaited rainfall.

He smiled, replaced his glasses, and rode on, happy about the prospect of doing a story on the first rain in Limi in two years. He could well imagine the upswing in the mood of the people. The prospect of filing a news story as an eyewitness filled him with joy as well.

Ordinarily Limi, with its mud houses, roofs brown with layers of dust, would be asleep. Now, however, Abel found the village in a frenzy. Everywhere, small groups of grownups showed their joy by praise-singing, as children ran around them in tattered clothes, their bodies pale and dirty.

In that atmosphere of elated expectations, Abel’s entry attracted no attention. Abel’s thoughts swung back and forth between noting landmarks and reviewing the unfolding drama. Limi, like most Nigerian villages, was inhabited by Christians, Moslems and animists, but on this day animism seemed to have the upper hand. The skies, hiding behind a conspiracy of clouds, appeared to be listening to worshippers who had refused conversion to Christianity or Islam.

Lightning lit the skies and people yelled in response to the volleys of thunder. These signs of rain would normally have sent people running indoors, but Abel saw villagers with bodies made white by drought and clothes dirty with dust pouring into the only street in the village.

He rode slowly, joining the celebration. Elsewhere such a situation would have resulted in bloody religious clashes, but here the tall, lanky Christian in a flowing gown got not so much as a glance as he walked in the opposite direction, warning against idol worshipping in a weak and cracked voice.

“God is a jealous God,” he said, “God gives rain, not man. God!” He rang a small, old, black bell with a makeshift handle as he tried to reach the crowd with his words. Abel resisted the temptation to talk to him and moved on.

After riding for ten minutes along the brown street, he followed people who had begun gathering around a big, shady nim tree. As Abel stopped his motorbike, he saw a sea of heads between him and the market square. A deafening quiet greeted him as the bike’s engine coughed and sputtered.

“Shhh. They are praying,” someone warned.

Abel turned to find the source of the whisper and saw a man of about twenty years old staring at him. He turned away and walked languidly in the direction of the market. Wearing an oversized brown shirt and black trousers, the thin youth had a powerful stride. His head was clean-shaven, showing his long occipital bone.

When the prayers ended, loud drumbeats and singing shattered the soothing quiet. Abel felt a jolt of excitement as he left his bike to join the crowd in the sandy market square. Numerous stalls, some with thatched roofs and some covered with sheets of steel, were scattered around the edges of the square. Abel stood in the partial shade of one roof to observe the scene. His height allowed him an unobstructed view of what was attracting and exciting the people.

In the market square was a short, scruffy-looking man about forty-five years old, prancing back and forth in and out of the cheering crowd, all the while tossing kola nuts into his mouth. Abel realized this must be Uzu Soto, the chief priest and rain charmer of the village.

But even before beginning his research on Limi, Abel had heard of this man. His primitive beliefs and his mystical hold on the village had been documented by his paper. Because of the drought, Soto had been interviewed on TV more than once. He had a large following among the elderly. He offered a simple solution to the unfolding tragedy. Prayer. And a simple explanation for its occurrence. Sin.

Soto danced hysterically to the drumbeat, celebrating the signs of the first possible rain in months. Despite his sparse, stained teeth, fierce, small eyes and wavy, unkempt hair, people in the crowd hailed him as “the favourite son of the gods.”

At another flash of lightning, Soto stopped in the middle of the circle and signalled the drummers to be silent while he examined the darkening skies. He nodded his approval and flashed his brown teeth in an infectious laugh of joy, drawing applause from the crowd. He nodded again, beat his chest with the short, stained staff in his hand and began to speak. The words hissed through large spaces between his teeth. Abel listened attentively.

“My people of Limi, Good people of Limi, sons and daughters of the gods of Limi!”

“Yeeeeee!” the people yelled.

Soto ingested more kola nuts, chewed quickly and continued.

“We have enemies. Yes, we have enemies – those who think the cause of our problems is something from the white man’s books. Even some of our own children belong to this group. They will be ashamed.

“They will be ashamed today. They will be ashamed because the rain will fall. It will fall now, my people!”

“Yeeehhhhh,” the people yelled.

Suddenly, as he stretched out his left hand, an aide planted a short black rod in his palm. The other end of the rod flamed like a torch. Soto danced around with the rod and stopped abruptly in front of Abel’s section of the crowd. He held the rod aloft and put his head back, sweat streaming down his face. Then he plunged the flame into his mouth and put it out. The crowd cheered.

The priest threw the rod away and received a live cock from another aide. The crowd fell silent. The cock must be the signal for silence, Abel thought as he saw people fall to their knees. He joined them in the graveyard stillness.

Soto stood motionless in the centre of the circle, holding the white cock and mumbling some incantation. When he dropped the cock moments later, it was dead. The crowd rose to its feet and burst into thunderous applause. Abel’s feigned excitement sent him crashing into the person to his right.

“Sorry, please,” Abel pleaded, impulsively holding the person by his shoulders. He turned out to be the young man who had hushed Abel earlier when he parked his motorbike.

“The clouds may have listened to him,” the young man said without seeming to have heard Abel’s apology.

More likely, he was consumed by the euphoria of the occasion, Abel thought to himself.

Just then, the sky exploded with flashes of lightning. Soto took a long bow, signalling for all to go home before the rains came.

Abel attempted to get the young man’s attention. “The rain will fall?”

“Oh, yes. You saw the cock. The gods always listen to Soto. He is our go-between,” the young man said, standing in Abel’s way as the crowd streamed around them. He stood his ground, defying the force of the throng, and then made his motive clear.

“My friend, God has blessed you. Kindly help me with some money to take care of the little ones at home.” The young man stretched out his right hand, the left tucked away in his pocket. His palm looked too soft and uncalloused for a village farmer, but the fingernails were long and dirty.

“Of course. But can you tell me where I can get a beer? Where do people gather?”

Abel figured if he was going to get hit up, he might as well get something in return. He wanted to mingle with the villagers in a place where there would be gossip. Many times he had scooped the crucial part of a story by chatting up the locals.

“Beyond the market square. The building with the red tin roof.”

Abel counted some money from his back pocket and dropped the high denomination naira notes into the outstretched hand.

“Thank you, my man,” the youth beamed and disappeared into the crowd. Abel headed in the other direction, towards the building with the red tin roof, just visible beyond the square.

á á á á á

For the next hour, Abel waited over a bottle of Guinness Stout in the beer bar just off the square, but the rains never came. The heavy clouds rolled away, leaving behind the sun, which beat down on the land once again. This failure drew comments from beer drinkers at the bar.

“Uzu Soto will not be disappointed,” one thin-looking man said. “He can make more sacrifices.”

“As we all saw, he almost got the rains down,” another replied. “If he makes continuous sacrifices, the gods cannot refuse him.”

“There were ample signs of his prowess at the market square earlier today,” Abel said. “But results are what counts. All I saw was a show. And, in the end, no rain.”

Abel wanted to prod discussion, see what the locals would say about the condition of the land. A young man sidled over.

“You don’t believe in our Soto? Perhaps you are rich.”

“Why do you say that? I’m merely asking a question.”

“Because the rich don’t worry about rain. They dig their own deep-water wells. Look up on the hill to the south of Limi, that’s where the rich live. With their wells. Here in the village, we suffer.”

Many in the bar nodded in agreement and this interested Abel. The whole question of wells was at the heart of his story.

“But surely the village can have a well.” An older man limped up using a single crutch. Abel noticed the lower half of his right leg was missing, the pants leg tied in a knot where the knee would have been. The man stared at Abel.

“It is easy for the rich to ignore the gods. They don’t need water. But this is what caused the drought. Men feeling no obligation to the gods. And the gods take our water to remind us who is in charge.”

Abel regarded this man, who was clearly angry and feeling impotent. His only hope was the prayers offered by Soto. Another man nearby slammed his glass of beer down hard on the table.

“Nonsense, my brother, nonsense. The gods are not watching. Our home is becoming a desert because men in other places are fouling the air. Don’t you read?”

The older man with the missing leg scowled. Abel watched them square off. He didn’t want this to degenerate into a brawl, so he interceded, saying, “I hear that this village was the food basket of the state until the drought. Obviously people here are divided about the cause of the misfortune.”

His observation defused the situation, their attention turned to him. The younger more cynical of the two said, “Food was no problem here. We grew enough to feed ourselves and sell to other towns. But suddenly, two years ago, after we had sown our crops, disaster struck. We waited and waited for rain, but not a drop. All we got was heat and dust.” He stopped to swallow. “The few educated people here, like myself, say it is because of the spread of desert conditions, but the preponderant view of elders and leaders in the village is that it is caused by the gods, who must have been offended.”

“Doesn’t the minister of agriculture come from here?” Abel decided to cast his net, let the men name Camp, but bring up his position.

“Camp? He does nothing. Why should he? His home is one of those with a well,” the young man spit out angrily.

The older waved him off. “Doctor Camp has been here many times talking with us. He understands what we must do.”

“He tells you to pray?” Abel asked, curious.

“No. But he listens and promises us better times. I believe him.”

“You would,” the young man said. He then drained his beer and moved off through the crowd.

Abel followed after him. “Can I ask you a few more questions?”

The young man turned. “Talking to me could be dangerous, you know.” Abel was surprised to hear this.

“You mean the village elders might not like us questioning their gods?”

“No. I mean the government has spies everywhere. I have been harassed before, because I speak out against them. They want these people to remain ignorant and to blame the gods for this drought. That way the politicians can continue to rob the public coffers and nobody stops them.”

“How do you know this?” Abel asked.

“It is well known,” the man said. “They drain bank accounts of public money and smuggle it to London, the United States, the Caribbean, where they spend it lavishly on their hedonistic lifestyles.”

“Lavishly? How?” Abel said, excited that he seemed to be making progress.

“Homes that are like palaces,” the man said. “Yachts large enough to circumvent the globe. Diamonds, emeralds and gold for their wives and mistresses. What some woman wear on one finger would pay for many deep wells.”

The information seemed too specific, the sins too great to be true. And how would this villager know? Abel asked him.

“My in-law is in the federal government in Abuja,” the man said. “He hears everything. Sometimes he tells me.”

“What about Doctor Camp?” Abel said. “Is he robbing you?”

The young man squinted, as if trying to see Abel’s face in the dim light of the bar. “Doctor Camp hasn’t helped us. We were to have a well here. Many wells. Nothing has happened.”

The man had not answered his question. “But is he stealing?”

“His father lives on the hill, and he comes to visit. I see him in the village. I see his face when he looks at the people. It makes him sad. No, I don’t think he steals. But he does nothing. He has water and doesn’t help us get water.”

Abel could have contradicted the young man. Camp was trying to help, he thought and he wished he could say something, but knew he could not. Nonetheless, he had heard what he most wanted to hear. Camp was honourable. He wasn’t playing Abel, wasn’t using him. Abel could trust him. That was the first thing a good reporter determined about a source. And now Abel could place his full trust in Camp. And he was just as certain that Camp was in danger. Or would be if he were exposed. Abel had to protect him, get the story and protect himself, all at once. Abel wished the man well and exited the bar. It had been a worthwhile trip after all.

Once outside, Abel decided to visit the other half of the equation. The witch doctor, Soto. He had overheard one of the men at the bar mention the location of his house. Abel knew witch doctors helped people with spiritual issues. He also knew that this man was considered unbalanced. It was part of what made him a believable conduit to the gods. But it was a reason for Abel to remain on guard.

Just before dusk, Abel found Soto sitting outside his small thatched hut at the far end of town. “Good evening, High One,” he greeted Soto.

Still chewing kola nuts, Soto was cheerful. “Welcome,” he whispered without looking up. “I have not seen you before. You must be a stranger.”

“Yes. I came to see you about a pressing spiritual problem.”

Soto’s eyes glowed. “Follow me and put the door back in place.” He limped briskly inside.

Inside was a circular shrine lit by a large old lantern. Abel sat on a stool opposite his host. Soto sprawled out on an animal skin, his feet spread wide apart. Around them there were piled idols, stones, gourds, calabashes and effigies smeared with blood.

“Now, my son, we have to hurry because of the rain,” Soto said to Abel’s disbelief, since the threat of rain had completely faded. But Abel played along. Soto poured a brown concoction from a small gourd into a calabash and rose to pray for Abel in his native language, circling the calabash around his head.

“You need this to embolden you to talk about all your problems. Some of my patients are very shy,” Soto said, offering the calabash to Abel. A loud thunderclap shook the hut as Abel took the foul-smelling container. Soto smiled.

The thought struck Abel that traditionally Soto should have tasted the concoction first.

Time to be careful, Abel thought, putting the calabash to his mouth. He found the opportunity he was looking for when he asked Soto to confirm that rain would fall that night.

“Rain? My son, it will rain.” Soto turned, making a sweeping gesture towards the effigies. Abel quickly poured the concoction away in the shadows beside him, grimaced to pretend he had tasted the bitter brew and held the calabash toward his host.

Soto refilled the calabash as thunder flashed again. “The god of rain, my sacrifice,” he mumbled as he shuffled towards an object in the shadows. “The god of fertility, my sacrifice, the god of rain, my sacrifice, the god of Limi, I thank you for accepting this offer already.”

In the faint light, Abel noticed they had company, a figure in the corner. He was stunned to see the man was the same young fellow who had shushed him during prayers and hit him up for money. Abel wished, for this fellow’s sake, that he had taken Abel’s gift and gone home to his family.

He was naked, slumped against the far wall, his legs folded in front of him and his head resting uneasily on his right shoulder. Soto raised the calabash to the young man’s mouth and he gulped the contents hungrily, his eyes squeezed shut.

“Loro, Loro,” Soto called him in a low voice. Loro could only summon a weak, sheepish look, and he laboured to take deep breaths.

Clearly, whatever Loro had drunk was having ill effects. Abel took the cue, cried out hysterically and slumped to his left.

“May the gods accept this sacrifice,” Soto said almost inaudibly. He pulled Loro in front of a large effigy of a human head and laid him on his back. Then he fetched a long, glittering knife from a shelf above the effigy.

“My gods,” he babbled, “for two years I have been making offerings of fowl and sheep, but you have rejected them and punished us with drought. Now I know what you want. Without my searching them out, you have offered two men. I know the rains will fall now. Two heads for you. I know, I know ….” He intoned more incantations, and then suddenly swiped the knife across Loro’s throat.

Abel shut his eyes and took in deep breaths he began to plan his escape. He hoped that Soto would not want to disrupt the sacrifice in order to chase him; so when Soto dropped the knife to hold a large calabash by Loro’s neck to collect the blood, Abel scrambled to his feet, pushed the thatched door open and ran out.

In the light of the quarter-moon, Abel stumbled ahead, barely able to breathe. He ran, adrenalin pushing his shaken exhausted body onward. After a minute or so, he came to what might have been a farm, now bare and dusty from the drought, and hopped over disused mounds. Tired after hopping over several mounds, he stopped to listen. He heard Soto reciting incantations far behind him, thought of that cruel knife and continued to run. He hoped he was running back to his bike. As he ran, he prayed he would make it out of this village without further incident.

At last, he recognised the tree under which he had left the bike. He made his way there and mounted it, hands shaking as he inserted the ignition key. He got the engine started before he noticed that the back tyre was flat. He could not be sure of the cause but suspected sabotage.

Abel cursed and clamped his sweating forehead in both hands. He felt overwhelmed. The sad sight of that poor fellow, his throat brutally slashed, haunted him. Finally, he gathered his strength and courage and pushed the disabled bike hurriedly along the road, scanning the horizon for signs of danger. At some distance from Soto’s hut, he stopped and looked around for help.

After a moment, a rugged-looking young man in a tight T-shirt and a baseball cap roared up on an old motorcycle. He showed no interest in Abel as he rode past him, but Abel could not let the opportunity slip by.

“Hello! Help me, would you?” Abel shouted, trying to keep a note of panic out of his voice.

The man stopped some metres away and turned. “What’s your problem, my man,” he said, coming toward Abel. The question was hostile, angry. When man reached Abel, Abel pointed to the flat tyre.

“My tyre…” But Abel never finished the sentence. The man punched him in the head. The blow sent Abel staggering backwards. Suddenly enraged, he responded with a fast, sharp uppercut to the villager’s chin. The young man crashed at his feet in a heap. Still furious, Abel dealt him a blow to the groin.

“Aaah,” the man moaned, coiling into a foetal position.

“What do they call you?”

“Mu . . . Mu . . . Muni. Please don’t kill me. I wanted your bike. I’m sorry. My family needs money. Please.”

Something about him was pathetic. Lying on the ground, he looked harmless. Less than harmless, a desperate starving man. The whole day came crashing down on Abel. The sight of so many poor people caught between a homicidal witch doctor and an indifferent criminal government made Abel deeply sad. Most if not all of the villagers would die exactly as they were today, poor and hungry. Most would never suspect how hopeless their situation was from the beginning.

Abel helped the young man to his feet. “Take the new bike. I’ll take your old one.” He strode over to Muni’s bike.

A whispered “Thank you” from Muni gave Abel a small measure of satisfaction as he kicked the old bike into life. The worn-out seat bit into him, and the engine faltered, but he managed to get out of the village. With a sense of relief, he rode unchallenged into the night.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.